We talk a lot in this blog about the uniqueness of Morocco Henna. From our research of henna designs from around the world and our conversations with henna artists (and other artists) from the region, we feel that we are onto something with this idea. Thanks to the Internet we’ve been able to see vintage photographs of women from all over North Africa, from around 1900 to the present. We have spent hours poring over hundreds — maybe thousands — of photos, zooming in on the people’s hands and feet to see if we can spy henna designs. I know this is some deeply nerdy stuff! But what can we say, we love henna, and we love researching about the history of Morocco henna.

Let’s start by describing what makes Morocco Henna so unique. Most people know that Moroccan henna tends to be very geometric, and has a lot of straight lines. There are also other styles of henna in Morocco that include flowers, vines, and leaves. In current iterations of Moroccan henna, you’ll see a lot of borrowing from South Asian and Gulf designs, changing the nature of what is “Moroccan”. From what we can tell, the geometric designs seem to be inspired by other women’s art forms, for example, embroidery (specifically the type from Fes), designs on household pottery, Amazigh tattoos, and kilims. The inspiration from these art forms seems very clear when you look at them side-by-side with Moroccan henna designs.

In our examination of vintage photographs from across the countries of North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt) we don’t see henna designs that are similar to the geometric ones we see in Morocco. What we do see is that across North Africa there was a tradition of applying henna with smears or dabbing or dipping. We have also seen evidence of designs made using resist techniques, where string or strips of fabric are wrapped around the hand in various ways, and then the henna is smeared over that. When the henna is removed it leaves the design behind. At a certain point, we can see where Morocco branched off from this style of henna, and started using sticks to apply henna (we will soon publish a story about the designs made with sticks), but we don’t see the same development in henna photos from other countries in North Africa at that time. Similarly, as Moroccan henna artists adopted the syringe to apply henna, we also don’t see this in any other country in North Africa. Now with the Internet and many connections amongst henna artists across North Africa, some of these countries’ artists have started using syringes and cones. This is especially true in the North African diaspora.

We have often wondered why there is this difference between Moroccan henna designs and those in the rest of North Africa. If you look at the women’s art forms across North Africa they have that same design vocabulary as Moroccan women’s art. Algerian and Tunisian rugs, household pottery, tattoos, etc. have those same motifs, and yet their henna artists did not create designs inspired by them.

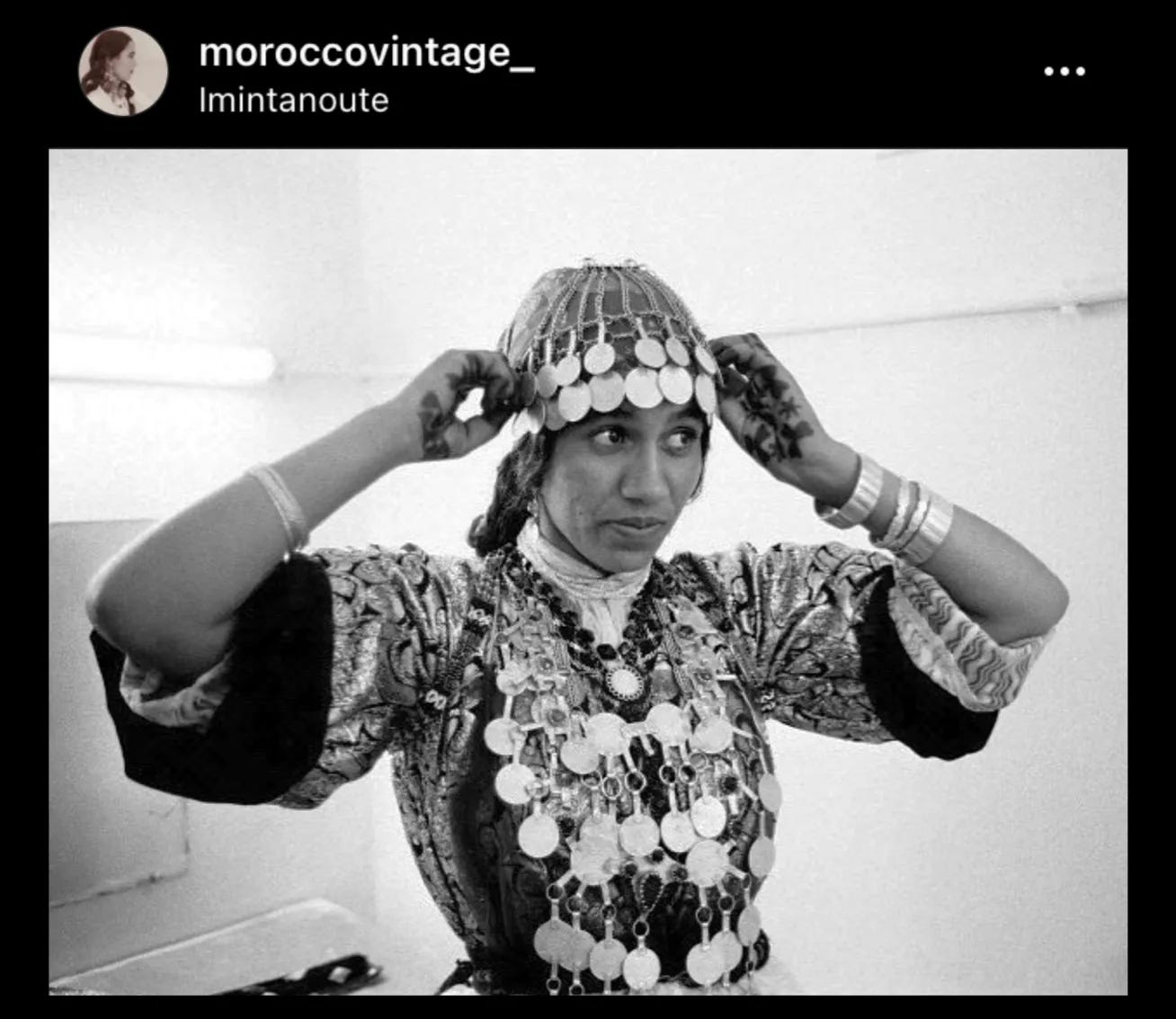

Just to remind you, this observation is based on our study of vintage photographs from and of North Africa. Many of these photos were taken by Western/French colonialists, and we can be sure that their view into the depths of these cultures was relatively shallow. Many western photographers would stage photos to make them look especially exotic, dressing up women in “traditional” outfits and jewelry that may not have been accurate for the culture of that person/region/era. Some of these photographs were pornographic and exploitative in nature. They made popular gifts for the folks back home to experience the “exotic creatures in faraway lands”. These photographs are relatively easy to discern from those that are more anthropological, or those photos taken by North African photographers. I mentioned this because there can be an issue when using photographs to make assumptions about a culture. Furthermore, henna stains remain on the skin for 2 to 3 weeks, so it’s unlikely that the application of henna was part of these staged photographs. Instead, it was probably accidentally present in them. It can also be seen in the photos of weddings or circumcisions.

Given all that we know about the nature of photography in North Africa, we can surmise that the representation of henna is relatively accurate. So what accounts for the development of Moroccan henna designs, and the very different path taken by other North African countries in their henna designs? Our theory is that it is the influence of the Ottomans. The Ottoman invasion of North Africa stopped just short of Morocco and definitely included most of Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. It’s hard to guess what impact that had on henna. But we can make some educated guesses by comparing other art forms among those countries under Ottoman rule and Morocco, which was not under Ottoman rule. For example, we can see that there are architectural similarities in these four Ottoman-controlled countries, and that those architectural styles in those countries are dissimilar to Moroccan architecture. We can look at other art forms in the regions, compare and contrast them, and see where these differences also reveal themselves. It doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to conclude that these differences carried over into other art forms in these countries.

Our theory is that Moroccan henna developed along its unique pathway because of indigenous Amazigh artistic influences mostly, but also with influences which came to Morocco from the Middle East via Spain… but not from the Ottomans. We believe that Moroccan henna came to be what it is because of these influences, as well as the tools that were adopted along the way, creating a style that does not exist in the rest of North Africa.

We could also talk about the development of styles in Mauritania and West Africa, which were also untouched by the Ottomans, but shared connections with Morocco, and even other parts of North Africa. But that could be too much!